Genetic testing is a highly effective tool for preventing hereditary diseases in many dog breeds. We have therefore prepared a specialized test panel for Collies (both Smooth and Rough), which includes all key conditions typical of this breed. In the following section of the article, you will find an overview and description of all diseases and monitored traits included in the Rough and Smooth Collie PACKAGE | genocan.eu

Collie eye anomaly (CEA) is a congenital developmental eye defect. Despite the name, it is most common in herding breeds (Rough/Smooth Collie, Shetland Sheepdog, Australian Shepherd, Border Collie and others). During embryonic development the choroid forms incompletely (choroidal hypoplasia) and in some dogs the retina is also involved. On fundus examination, changes are typically seen close to the optic disc as a paler or thinner area; colobomas may occur in more severe cases. Puppies should ideally be examined at 7–8 weeks of age, because after about 3 months lesions can become difficult to recognize due to pigmentation (“go-normal”). Inheritance is autosomal recessive, but clinical severity is highly variable, and mildly affected dogs may appear normal on later exams.

PRA-rcd2 (rod-cone dysplasia type 2) is an inherited retinal disease seen mainly in Rough and Smooth Collies. It is an early-onset, rapidly progressive form of PRA. In affected puppies, development of rods and cones is abnormal: photoreceptor maturation arrests prematurely and is followed by fast degeneration. The first clinical sign is typically night blindness at around 6 weeks of age (hesitation in dim light, bumping into objects). Vision then deteriorates quickly, and most affected dogs become functionally blind between 6 and 12 months of age. Inheritance is autosomal recessive, meaning clinical disease occurs when a dog inherits two mutated alleles; carriers are usually clinically normal.

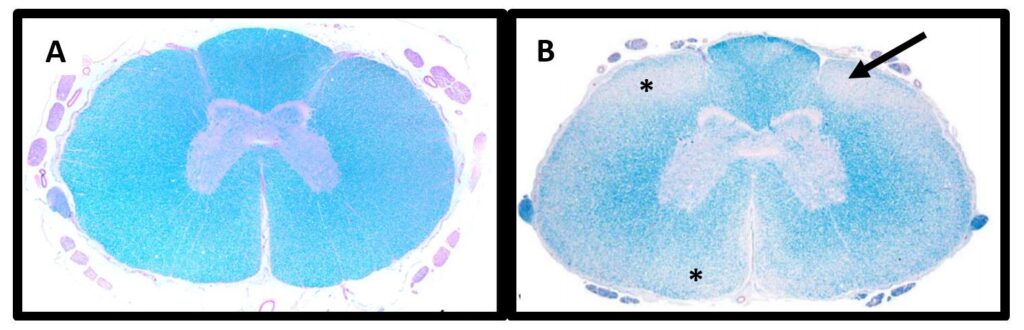

Degenerative myelopathy (DM) is a progressive, incurable spinal cord disease, most often affecting older dogs (commonly around 8 years) and both sexes equally. Early signs include hind-limb incoordination, scuffing of the nails and mild weakness. Over time, ataxia and muscle atrophy develop; advanced disease may lead to urinary or fecal incontinence and gradual loss of hind-limb function, eventually paralysis. DM is associated with a variant in the SOD1 gene. It is generally inherited as an autosomal recessive trait with variable penetrance: dogs with two risk alleles are at high risk, but not all will develop clinical disease. A DNA test cannot reliably predict age of onset or how fast the condition will progress.

Reference: Awano T, et al. PNAS (2009). 106(8):2794-2799 and March PA, et al. Vet Path (2009). 46:241-250.

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a rare skeletal-muscle disorder that is usually silent in everyday life but can be triggered by certain anesthetic agents (e.g., halothane, isoflurane or sevoflurane). An episode involves uncontrolled muscle activity with rigidity, tachycardia and a rapid rise in body temperature. Without prompt intervention, complications may include arrhythmias, rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney failure and death. If MH is suspected, anesthesia must be stopped immediately, the patient actively cooled and specific therapy to reduce muscle contraction administered. For dogs known to be at risk, alternative anesthetic protocols that avoid triggering agents can be used. In dogs, MH is commonly described as autosomal dominant, so a single mutant allele may be sufficient and the risk to offspring is about 50%.

Multiple Drug Resistance (MDR1) is an inherited drug-sensitivity trait common in Collie-lineage and other herding breeds. A variant in the ABCB1 gene reduces or abolishes P-glycoprotein function, an efflux transporter at the blood–brain barrier and other tissues. Normally, P-glycoprotein limits entry of certain drugs into the brain; when impaired, these compounds can accumulate and cause neurotoxicity. Drugs of concern include high-dose ivermectin, loperamide, some sedatives/analgesics (e.g., acepromazine, butorphanol) and certain chemotherapy agents. Clinical signs may include hypersalivation, weakness, ataxia, tremors, seizures, blindness and, in severe cases, respiratory depression or death. Dogs with two mutant alleles are at highest risk, but heterozygous carriers may also react to some drugs or doses, usually more mildly.

Inflammatory pulmonary disease in Collies (IPD) is an inherited syndrome described mainly in Rough Collies. It is characterized by recurrent episodes of lower-airway inflammation and bronchopneumonia. Signs can begin in very young puppies and may include coughing, rapid or labored breathing, nasal discharge, fever and sometimes repeated foamy vomiting. Many dogs improve with antibiotics and supportive care, but relapses are common once treatment stops, so the course can be chronic and markedly reduce quality of life. Inheritance is autosomal recessive: affected dogs inherit the causative variant from both parents, whereas carriers are typically clinically normal. For breeders, identifying carriers helps avoid producing affected puppies while preserving genetic diversity.

Cyclic neutropenia (CN), also called Gray Collie syndrome or cyclic hematopoiesis, is a severe inherited disorder of Rough and Smooth Collies. It is a bone-marrow stem-cell defect causing periodic fluctuations in blood cell production, most notably profound neutropenia. In 10–12-day cycles, affected puppies experience several days of very low neutrophil counts and are highly susceptible to bacterial infections. Clinical signs may include fever, lethargy, diarrhea, bronchopneumonia, skin and mucosal infections, joint pain and sometimes bleeding tendencies as other cell lines fluctuate. Dilute gray coat pigmentation is characteristic. Prognosis is generally poor; many affected dogs die young even with intensive care. Inheritance is autosomal recessive, so affected puppies inherit the variant from both parents.

Locus-L (long coat) is a genetic test for coat-length variants in theFGF5 gene. FGF5 is a key regulator of the hair cycle, helping end the growth phase (anagen) and shift follicles into regression (catagen). When FGF5 function is reduced, the growth phase is prolonged and hairs can grow longer, producing a long coat. Several recessive FGF5 variants have been described in dogs; a long coat is typically expressed when a dog inherits two long-coat alleles (in any combination). Inheritance is therefore autosomal recessive: carriers are usually short-coated but can produce long-coated offspring when bred to another carrier. For breeders, testing helps predict coat type in litters and avoid unexpected long-coated puppies when this is undesirable.